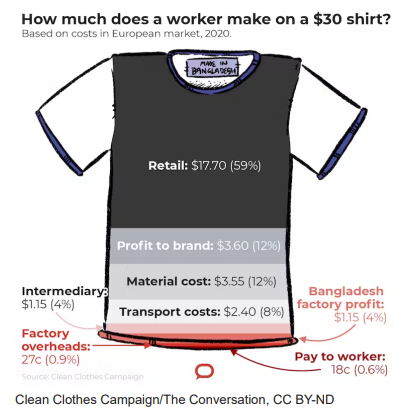

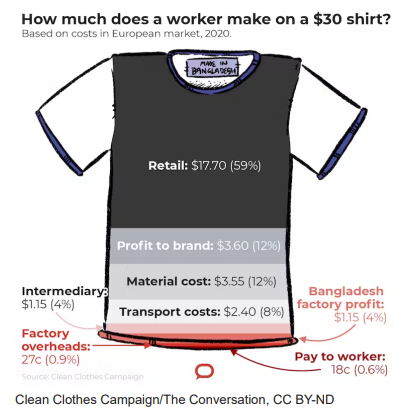

Figure A: Production costs of a $30 USD shirt

Source: Rahman, S. & Yadlapalli, A. (2021). Years after the Rana Plaza tragedy, Bangladesh’s garment workers are still bottom of the pile. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/years-after-the-rana-plaza-tragedy-bangladeshs-garment-workers-are-still-bottom-of-the-pile-159224

Figure A shows that only 0.6% of the total net cost is earned by a worker producing a $ 30 USD shirt based on costs in the European market, 2020.

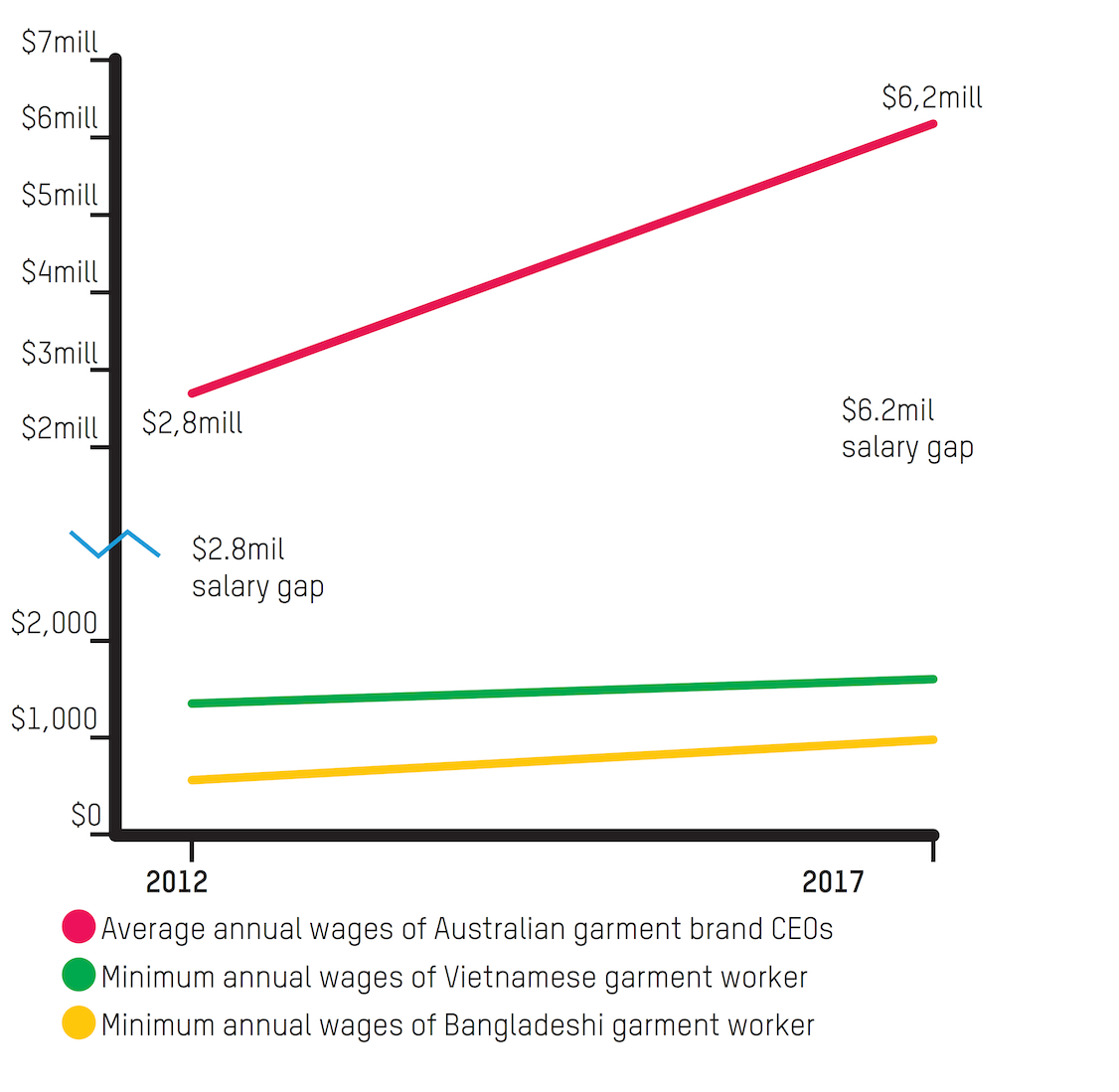

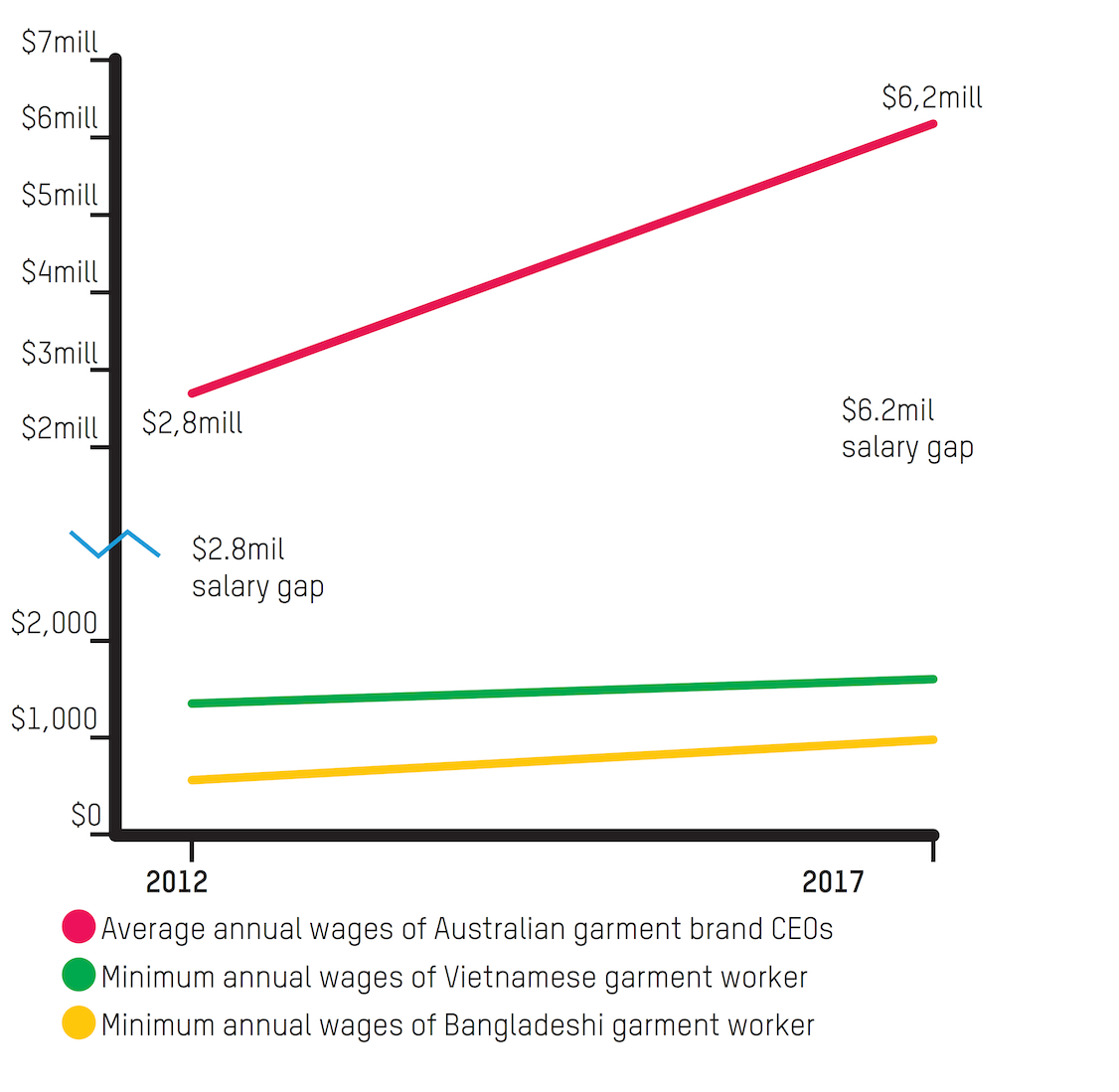

Figure B: Salary gap between Australian CEOs and Bangladeshi garment workers

Source: Oxfam Australia. (2018). Growing gulf between work and wealth. Australian Fact Sheet.

https://www.oxfam.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/2018-Davos-fact-sheets.pdf

As a result of the high demand worldwide to keep prices low for clothing manufacturers, only 0.6% of the retail price of a t-shirt goes to the worker (see Figure A) (Rahman & Yadlapalli, 2021). This disparity creates a huge salary gap between CEOs and Bangladesh garment workers. According to Oxfam Australia, a CEO in a top fashion company in Australia earns up to $2,500 per hour, whereas a garment worker earns only the legal minimum wage of $0.39 AU per hour (see Figure B) (Brungs, 2023). The low wages of Bangladesh garment workers has created serious socio-economic problems for the worker and their family resulting in a life threatening struggle to make ends meet (The Borgen Project, 2023).

The average shift of a Bangladeshi garment worker is 10 hours per day, with a short break (Balachandran, 2019) and when there are large orders to fulfil during peak times, they are frequently forced to work overtime (The Borgen Project, 2023).

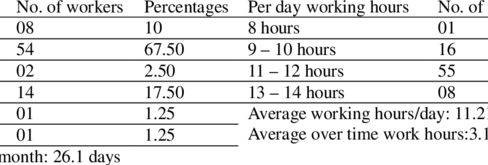

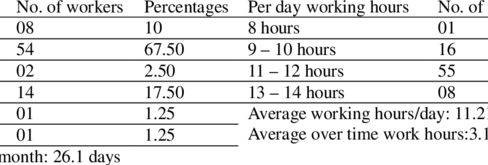

Table A: Working days and working hours per month of female garment workers in Dhaka City

Source: Sikdar, M. M.H., Sarkar, M.S.K., & Sadeka, S. (2014). Socio-Economic Conditions of the Female Garment Workers in the Capital City of Bangladesh. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 4(3). https://www.ijhssnet.com/journals/Vol_4_No_3_February_2014/17.pdf

According to a study by Sikdar, Sarkar and Sadeka (2014) the average working hours per day is more than 11.21 hours for garment workers. Sometimes they work 14-16 hours, 7 days a week (Oxfam Australia, 2019). Due to these long working hours the garment workers have an increased the risk of injuries, disease, and mental health problems (Wong et al., 2019).

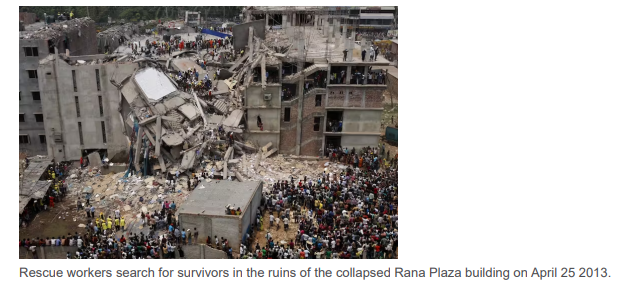

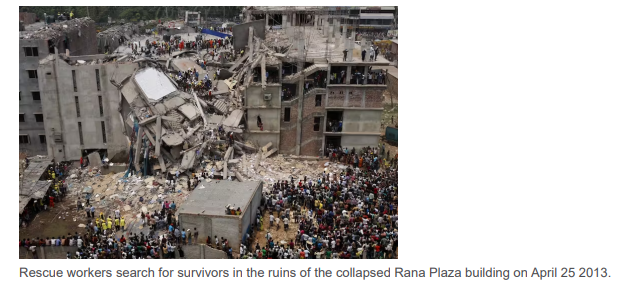

Figure C: Biggest industrial tragedy in Bangladesh: Rana Plaza collapse in 2013

Source: Rahman, S. & Yadlapalli, A. (2021). Years after the Rana Plaza tragedy, Bangladesh’s garment workers are still bottom of the pile. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/years-after-the-rana-plaza-tragedy-bangladeshs-garment-workers-are-still-bottom-of-the-pile-159224

Figure D: Images of unsafe working conditions inside garment factories in Banglade

Source: Wadud, Z., & Huda, F. Y. (2017) Fire safety in the readymade garment sector in Bangladesh: structural inadequacy vs. management deficiency. Fire Technology, 53 (2). 793-814. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10694-016-0599-x

Figure D shows that unsafe working conditions inside garment factories, such as, stairways, exit doors, and exit conditions do not follow safety regulations in Bangladesh.

The biggest industrial tragedy to ever affect the clothing industry in Bangladesh occurred in 2013 (Figure C), when a garment factory in Dhaka collapsed, killing over 1,100 people and injuring 2,600 more, because they ignored the building codes (Rahman & Yadlapalli, 2021). Most of the factory regulations for inside the building were not adhered to (see Figure D) (Wadud & Huda, 2017). After the incident, the industry promised to improve. A month later, 222 companies agreed to the legally binding Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety, which was created to protect garment workers at work (Rahman & Yadlapalli, 2021).

Confusion by Leanne Lindsay

Confusion by Leanne Lindsay Composition in between of a Red by Taufik Gustian

Composition in between of a Red by Taufik Gustian